In an era of rapid industrial transformation and growing environmental urgency, the fate of British Steel has become more than just a national concern—it’s a symbol of how traditional industries must evolve to survive. The recent UK government intervention to take control of British Steel, averting the closure of the country’s last two blast furnaces in Scunthorpe, marks a defining moment in the steel industry. This dramatic development offers critical insights into the delicate balance between economic viability, energy efficiency, and sustainability—a conversation that resonates far beyond British shores and holds lessons for steel manufacturers and policymakers around the globe.

At Lux Metal, as Malaysia’s forward-thinking leader in customized metal solutions and stainless steel manufacturing, we believe it’s vital to explore these global industrial shifts. Understanding how the UK is planning to revive its historic steel sector helps frame the future for emerging and established steel producers alike—especially those aiming to stay competitive and carbon-conscious in a demanding global market.

The Turning Point: Government Steps In

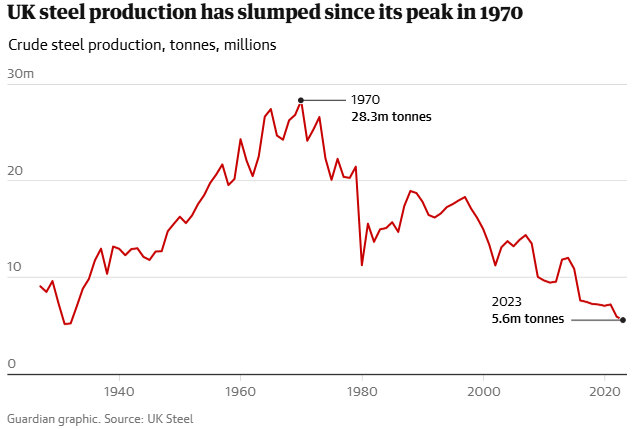

British Steel’s journey over the past decade has been turbulent. Once a symbol of industrial might, the company has undergone a series of ownership changes, from Tata Steel to Greybull Capital in 2016 (for a nominal £1), then to Chinese group Jingye Steel in 2019. However, after consistent financial losses, Jingye recently announced the closure of British Steel’s blast furnaces in Scunthorpe—an action that would have effectively ended the production of primary or “virgin” steel in the UK.

Faced with imminent shutdown and the potential loss of thousands of skilled jobs, the UK government made an unprecedented move. Through emergency legislation, it took control of the assets, extending a lifeline to the Scunthorpe plant. While the takeover provided a temporary reprieve, it raised a pressing question: what comes next?

The answer may lie in how the industry reinvents itself—not only to remain profitable but also to drastically reduce emissions and align with the UK’s net-zero goals.

Decarbonizing Steel: The Rise of Electric Arc Furnaces (EAF)

The global steel industry is one of the largest industrial sources of carbon emissions, largely due to its reliance on traditional blast furnaces. These units consume coal to reduce iron ore into molten iron, emitting massive quantities of CO₂ in the process. Scunthorpe’s blast furnaces are no exception, and their closure—though controversial—represents an opportunity for reinvention.

The future for British steelmaking increasingly points toward electric arc furnaces (EAFs), which use high-voltage electricity to melt down scrap steel rather than raw iron ore. This method can cut emissions by more than half and is already widely adopted in parts of Europe and North America. In the UK, Tata Steel’s decision last year to replace its blast furnaces in Port Talbot with EAFs set a precedent. British Steel’s Scunthorpe site is now likely to follow a similar path.

EAFs are particularly well-suited for urbanized, developed economies like the UK, where vast quantities of recyclable steel are readily available from decommissioned buildings, vehicles, and machinery. Unlike virgin steelmaking, EAF operations align with circular economy principles, making them more sustainable and adaptive to future carbon regulations.

Trade protectionism

Government policy on the steel industry has been pulled between the desire for a free market and state control for most of the past century. Clement Attlee’s Labour government nationalised the steel industry in 1949, and then the Conservatives privatised it in 1951. Labour renationalised it in 1967 and Margaret Thatcher privatised it in 1988.

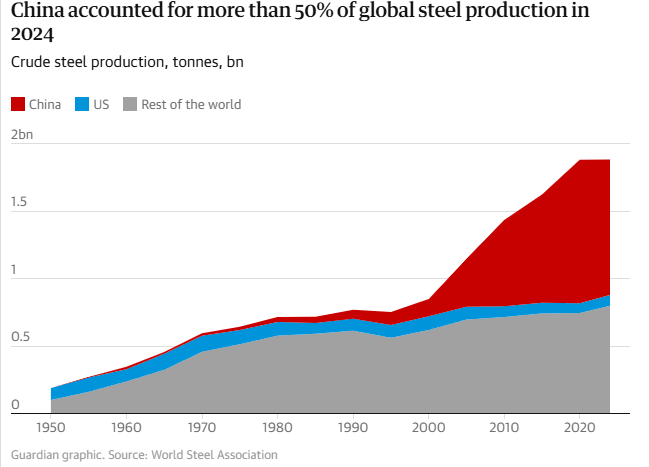

Many people in the steel industry argue that it has never really been a free market. Too many governments tip the scales to support strategic industries. Now that the free market is in retreat around the world, thanks in part to Donald Trump’s tariffs, the steel industry insists that protectionism is necessary for the UK industry to survive.

Quotas set in response to Trump’s first-term tariffs are now bigger than demand, leaving them out of date, said one senior UK steel executive. British companies allege that foreign rivals are dumping steel in the UK in their desperation to find a buyer. The industry wants the UK government to react to trade distortions sooner.

“We need to be quicker,” said the executive. “We’re suffering a serious diversion of trade from EU and other countries, and prices no longer follow EU levels as has been the norm for many years.”

Challenges in the Transition

While the move to EAFs makes environmental and economic sense, it is not without challenges. Several critical hurdles must be addressed:

1. Energy Costs

British industry leaders are vocal about one major barrier: the cost of electricity. UK-based steel producers pay approximately £68 per megawatt-hour (MWh) for power—significantly more than their European counterparts. France and Germany, for instance, offer industrial electricity at £44 and £52 per MWh, respectively. Sweden, with its abundant hydroelectric capacity, offers it for even less.

For EAFs to be economically viable, especially when scaled up across British Steel’s infrastructure, the UK must urgently reform its energy market and ensure competitive rates for industrial users. Subsidizing energy for critical industries could be one solution. According to UK Steel, leveling the playing field with European countries would cost households less than 50p per year.

2. Scrap Metal Management

Despite producing 10–11 million tonnes of scrap metal annually, the UK exports a significant portion of it to countries like Turkey. If British Steel is to run efficiently on EAFs, the government must introduce policies that incentivize domestic recycling and discourage the export of valuable scrap.

A secure supply of locally-sourced steel scrap ensures cost efficiency and supply chain resilience—an essential factor if the UK wants to maintain self-sufficiency in times of geopolitical or economic disruption.

3. Workforce Impact

EAFs require fewer workers than traditional blast furnaces, raising concerns about employment. Trade unions like the GMB are calling for retraining programs and phased transitions that protect skilled jobs. Alternatives such as hydrogen- or methane-powered furnaces, which could retain more existing infrastructure and jobs, have also been floated, although they are less mature and potentially less economically viable at scale.

4. Infrastructure and Investment

The UK government has pledged £2.5 billion to support the steel industry. Industry leaders and unions are pushing for two key investments: a large-scale plate mill to support the wind turbine supply chain, and a Direct Reduced Iron (DRI) plant to produce low-carbon iron using hydrogen or methane.

These projects could strengthen the UK’s industrial base, support its renewable energy ambitions, and ensure that domestic steel plays a central role in critical national projects—such as defense, infrastructure, and energy.

Alasdair McDiarmid, assistant general secretary at Community, another union representing steelworkers, called for two big projects backed by the UK government. The first would be a large plate mill that would be capable of making the steel needed for wind turbine towers needed for the government’s expansion of green energy. Only 2% of the steel used in British offshore wind projects over the past five years was made in the UK, according to Lumen Energy & Environment, a consultancy.

If that proportion does not rise then the UK will miss out on up to 2m tonnes of demand at the peak. The government is thought to be prepared to pay higher prices for British steel if it supports jobs in the UK, a consideration that will also inform the planned defence spending boom.

The second big investment would be a factory making direct reduced iron (DRI). That would use methane and then, ideally, hydrogen made with clean electricity, to produce iron from iron ore, thereby almost eliminating the need for coal in virgin steel production.

DRI plants already produce millions of tonnes a year using methane, with India the biggest producer of lumps of iron known as hot briquetted iron.

The unions may be pushing at an open door. The government has made clear that it is seriously considering DRI. It has received a report on the technology by the Middlesbrough-based Materials Processing Institute, formerly a research arm of Tata Steel, and ministers have talked of DRI’s potential for several years.

Jonathan Reynolds, the business secretary, told parliament on Saturday: “I believe that the capacity for primary steel production is important. Direct reduced iron technology is of significant potential interest to us for the future.”

What that would look like is unclear, however. None of the major steel companies in the UK has expressed a desire to run a DRI plant, despite government waving the possibility of huge subsidies. A person with knowledge of the government’s thinking said it was likely that a commercial partner would be sought to build a DRI plant, if recommended in a study by the Materials Processing Institute.

Strategic Sovereignty and Industrial Resilience

One argument for preserving primary steelmaking in the UK is strategic autonomy. As recent global events have shown—from the pandemic to supply chain disruptions and war—reliance on imports can create vulnerabilities in national security and critical infrastructure.

The UK’s steel industry is essential not only for economic output but also for defense readiness and infrastructure development. For instance, during the COVID-19 crisis, Tata Steel’s facilities were crucial in maintaining the supply of food cans—a seemingly small but essential item.

A long-term vision for British Steel must ensure that the UK retains the capability to produce specialized and high-grade steels, even if bulk commodity steel production becomes less central. This could mean focusing on niche segments like aerospace-grade alloys, reactor steel for submarines, or infrastructure-grade long products.

What It Means for Global Players Like Lux Metal

At Lux Metal, we’re closely watching the UK’s efforts—not only because it signals shifts in the global steel landscape, but also because it provides a blueprint for innovation and survival in a sector under pressure.

Malaysia, like many industrializing nations, faces its own challenges in transitioning to greener steelmaking processes. Rising electricity prices, environmental regulations, and international trade dynamics all play a part. The UK’s model demonstrates the importance of government-industry collaboration in navigating these pressures.

Lux Metal’s commitment to sustainability and innovation has already positioned us as a leader in Southeast Asia’s stainless steel sector. Our adoption of advanced machinery—from laser cutting and bending machines to precision CNC systems—ensures that we remain ahead of the curve in productivity and precision.

Yet the UK’s experience reminds us that even well-equipped companies must stay adaptive. New technologies, such as hydrogen-based steelmaking or enhanced scrap recovery systems, could eventually redefine what efficient, eco-friendly production looks like. Preparing for that future, through continuous investment in R&D and government dialogue, will be key.

The Bigger Picture: Steel and National Identity

British Steel’s saga is not just about economics—it’s about national pride, industrial identity, and political will. It’s a testament to the steel industry’s symbolic value as a cornerstone of modern development. The same ethos applies to nations like Malaysia, where steel remains vital for infrastructure, housing, and manufacturing.

Governments worldwide will need to balance free-market principles with strategic interventions. With global trade facing increasing protectionism, countries that support their domestic industries while ensuring fair competition will have the upper hand.

Looking Forward: A Blueprint for the Future

As British Steel stands at the cusp of transformation, it’s clear that the path forward will require innovation, investment, and compromise. The Scunthorpe plant may no longer burn coal to produce molten iron, but it can still serve as a beacon of what a modern, responsible steel industry should look like.

For companies like Lux Metal, the takeaway is clear:

- Embrace sustainable manufacturing technologies.

- Collaborate with governments and stakeholders to shape smart policies.

- Strengthen domestic supply chains and scrap recycling programs.

- Stay agile and responsive to global shifts in trade, energy, and environmental standards.

British Steel’s story may be one of last-minute salvation, but with the right steps, it can become one of renewal and resilience. For the global steel community, this is more than news—it’s a signal that the next chapter in industrial evolution has begun.

At Lux Metal, we fully support fair trade practices and the protection of Malaysia’s local manufacturing industry. As a leading provider of customized metal fabrication services in Malaysia, Lux Metal is committed to:

✅ Precision stainless steel works

✅ Advanced CNC machining

✅ Customized structural and industrial metal solutions

✅ End-to-end service from design to delivery

Whether you’re in construction, manufacturing, or industrial sectors, we’re here to provide cost-effective, reliable, and high-quality fabrication — helping Malaysian businesses stay competitive in a globalized economy.

🔗 Explore our services at Lux Metal

📞 Contact us for tailored solutions to your project needs

Conclusion:

The UK government’s timely intervention in British Steel’s crisis has not only prevented the imminent shutdown of Scunthorpe’s blast furnaces but has also reopened the national conversation about the future of domestic steelmaking. This moment is a critical inflection point—where political will, economic strategy, environmental responsibility, and industrial innovation must align to determine what comes next.

As the country considers a pivot from coal-based production to electric arc furnaces and possibly Direct Reduced Iron (DRI) technology, one thing is clear: the future of steel must be both economically viable and environmentally sustainable. But it will require more than just government subsidies—it will demand coordinated action across energy reform, trade protection, local scrap management, and industrial infrastructure. The challenge is significant, but so is the opportunity.

For manufacturers like Lux Metal and others in Southeast Asia, this serves as a powerful case study. It’s a reminder that industry transformation isn’t just about technology—it’s about timing, bold leadership, and long-term strategic planning. Whether it’s for infrastructure, clean energy, or national defence, the steel we shape today will build the world we live in tomorrow.

References:

- The Guardian. (2025, April 17). British Steel is safe – for now. What comes next will decide if it is sustainable. Retrieved from The Guardian